Opening Quote

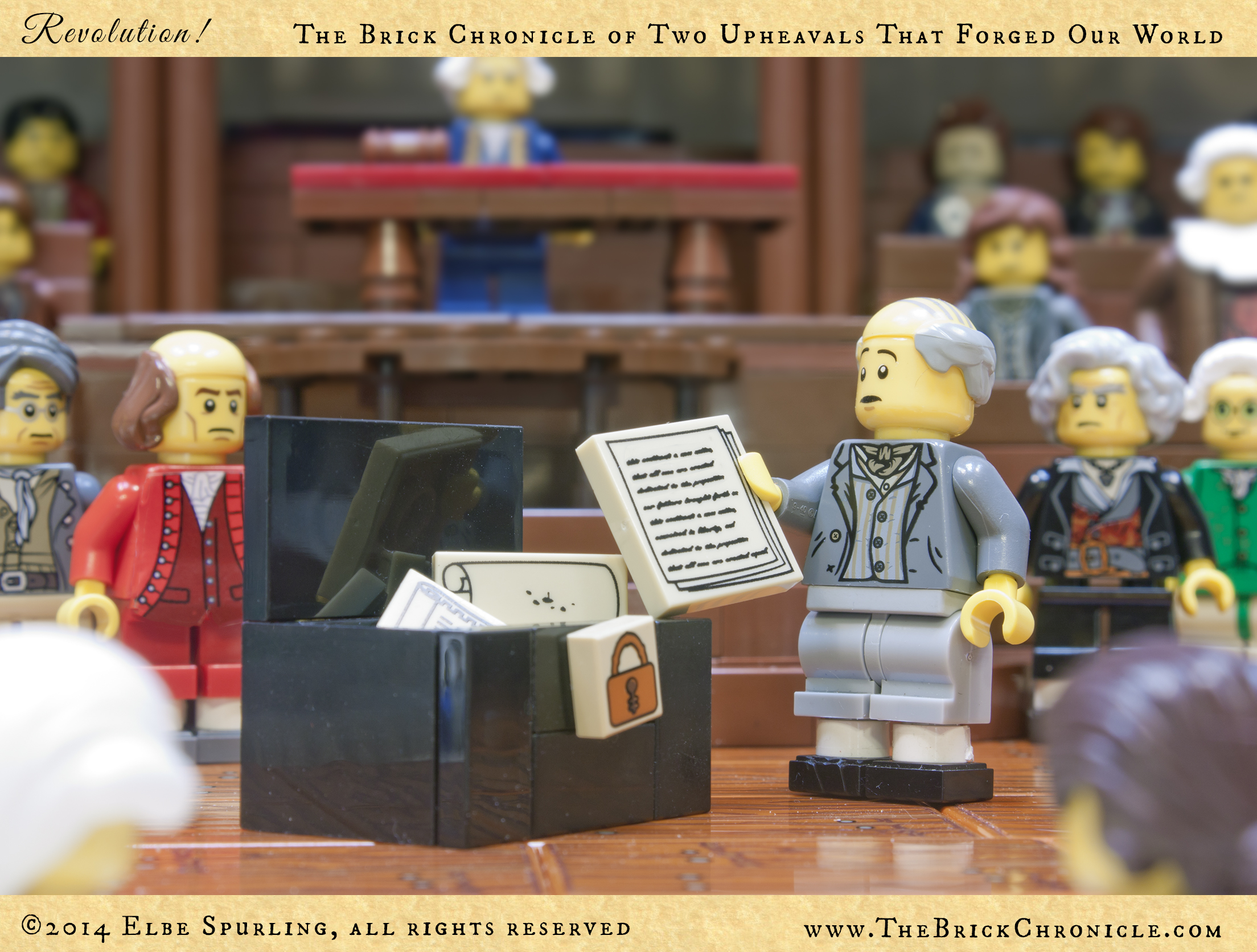

chapter_13_image_01

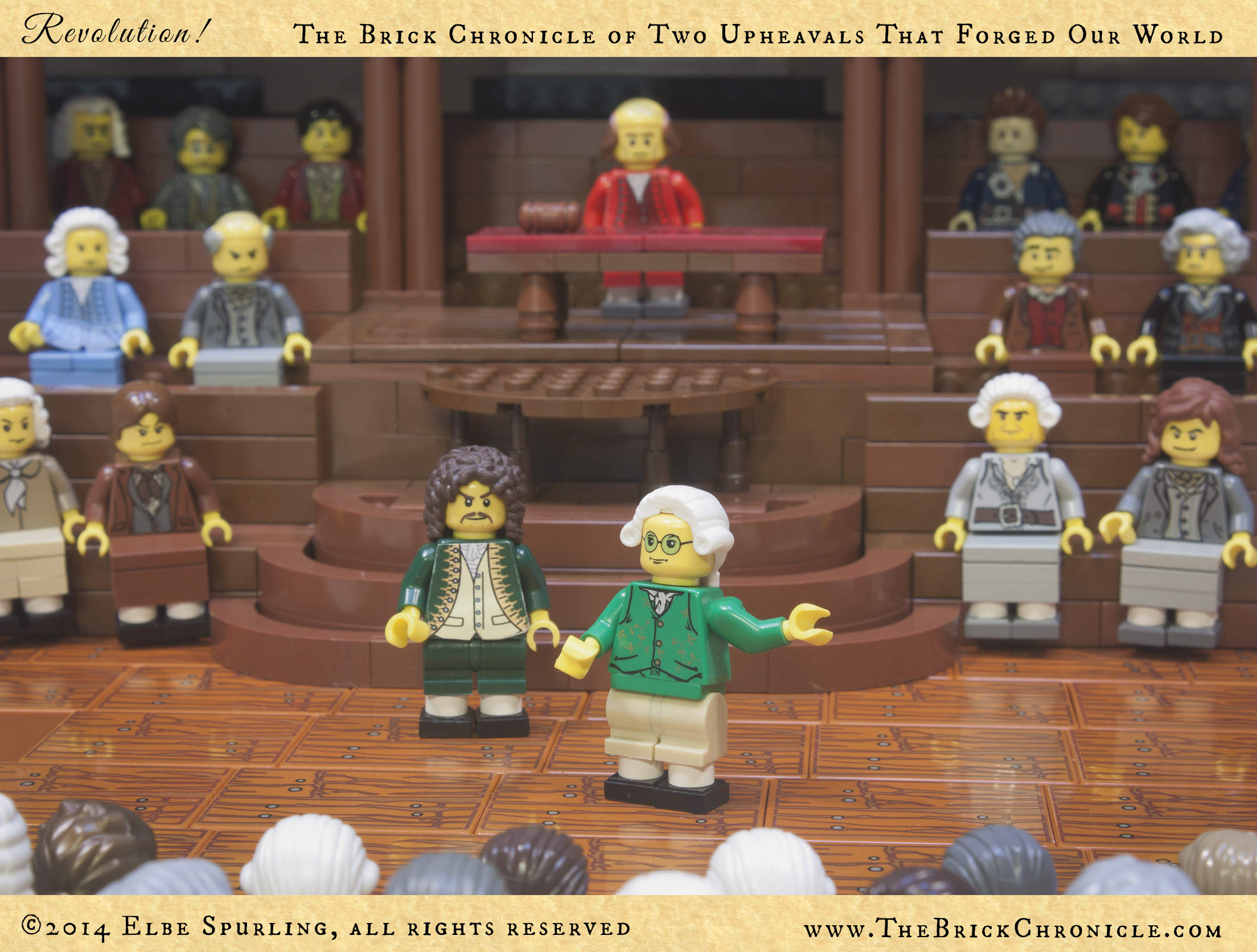

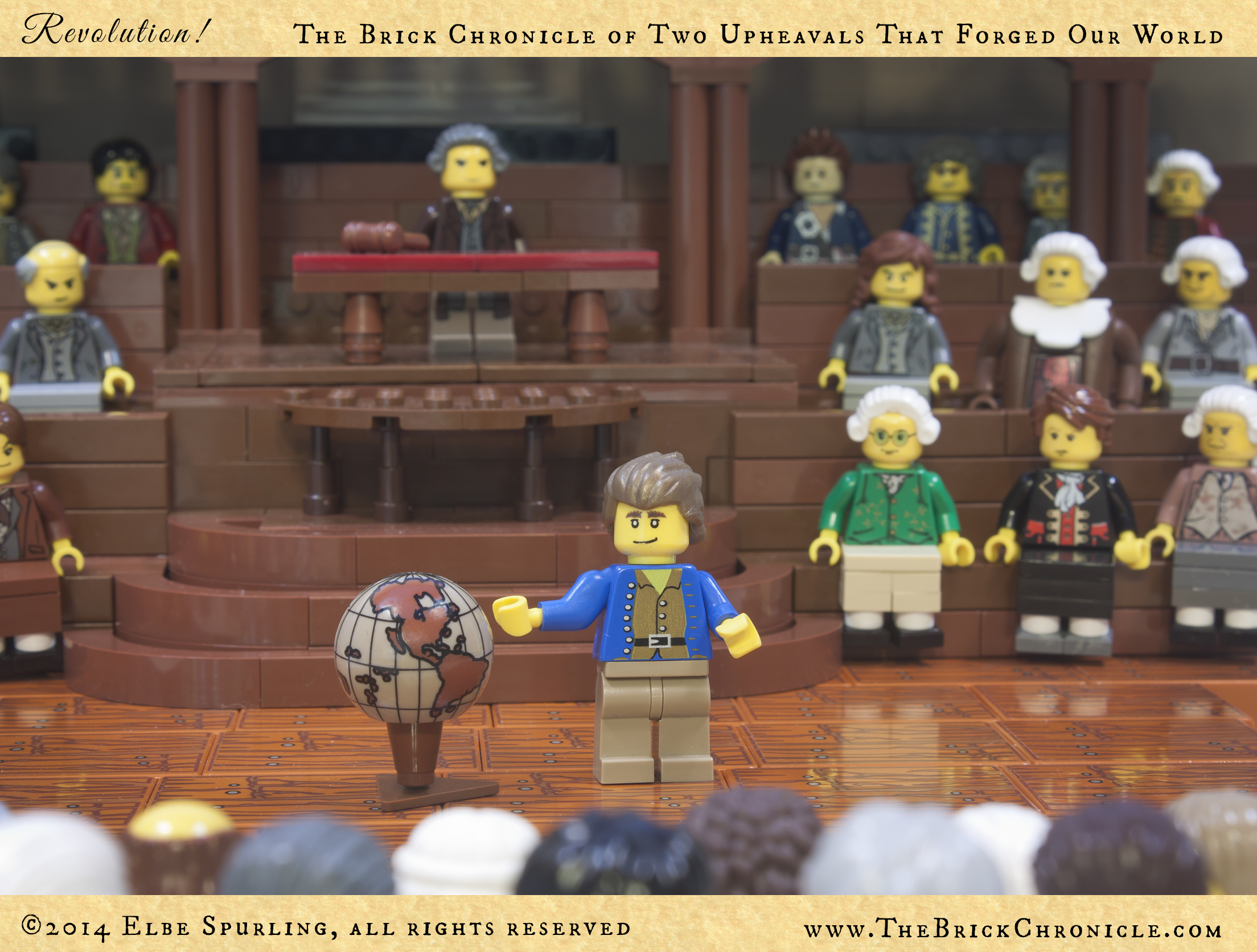

chapter_13_image_02

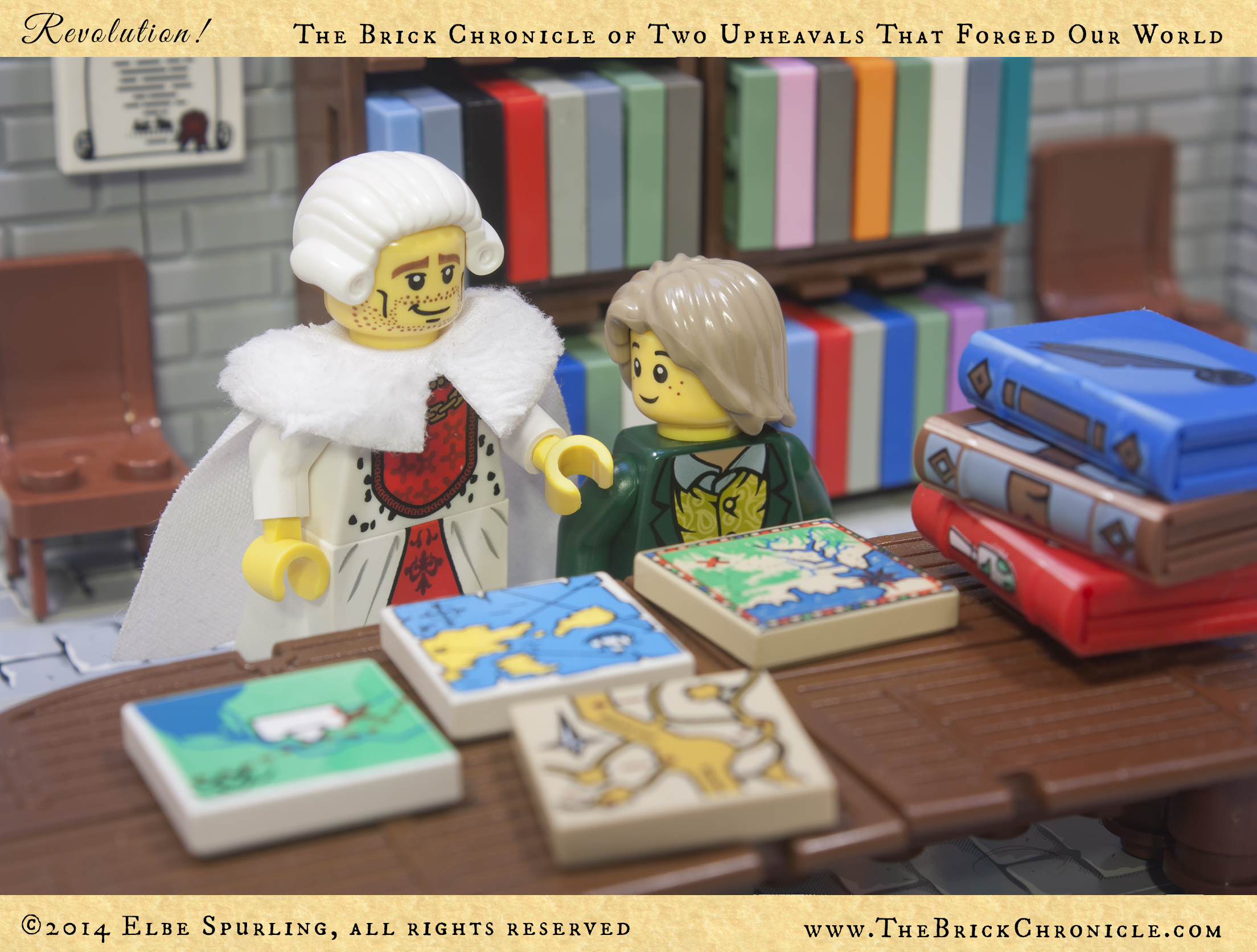

chapter_13_image_03

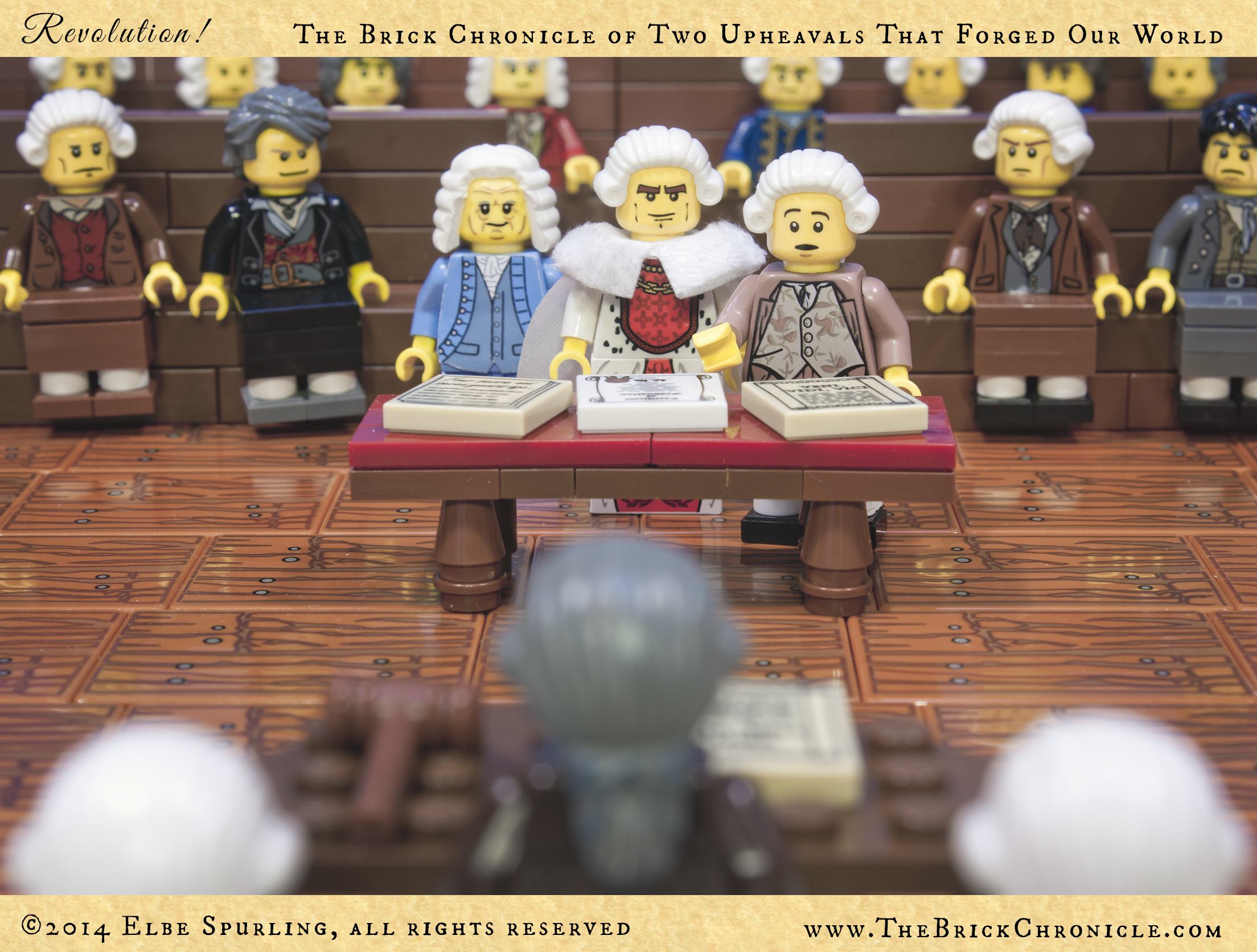

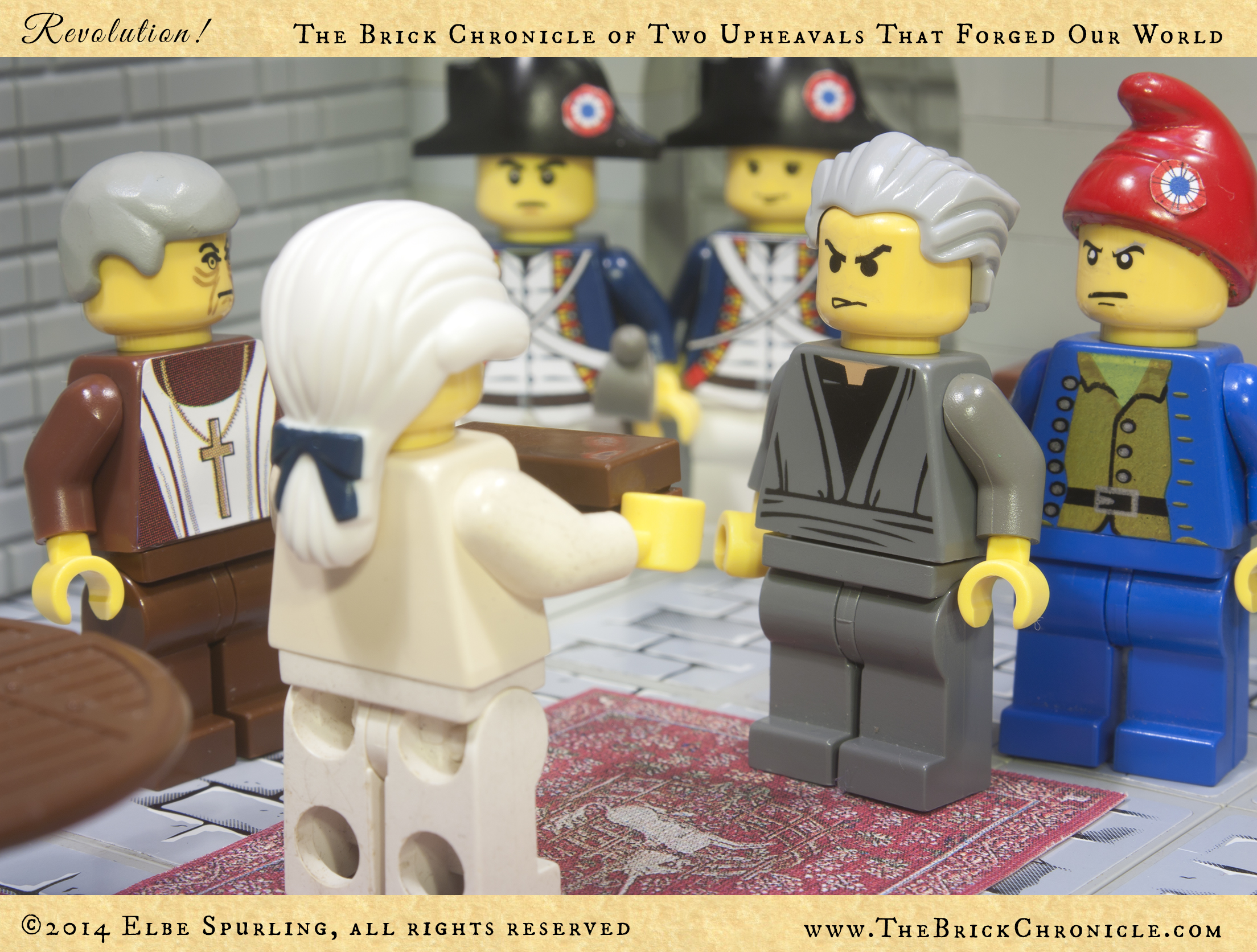

chapter_13_image_04

chapter_13_image_05

chapter_13_image_06

chapter_13_image_07

chapter_13_image_08

chapter_13_image_09

chapter_13_image_10

chapter_13_image_11

chapter_13_image_12

chapter_13_image_13

chapter_13_image_14

chapter_13_image_15

chapter_13_image_16

chapter_13_image_17

chapter_13_image_18

chapter_13_image_19

chapter_13_image_20

chapter_13_image_21

chapter_13_image_22