Opening Quote

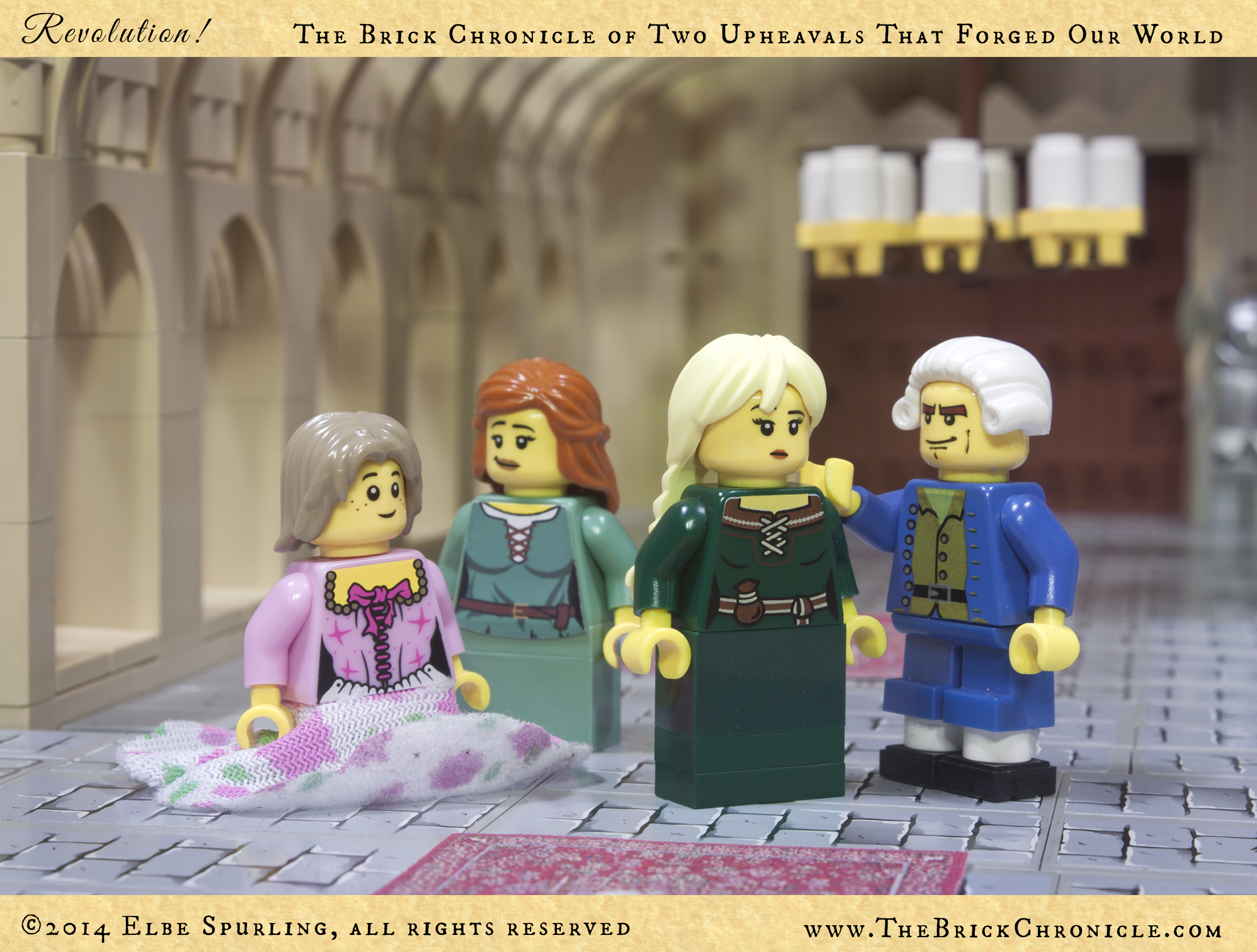

chapter_11_image_01

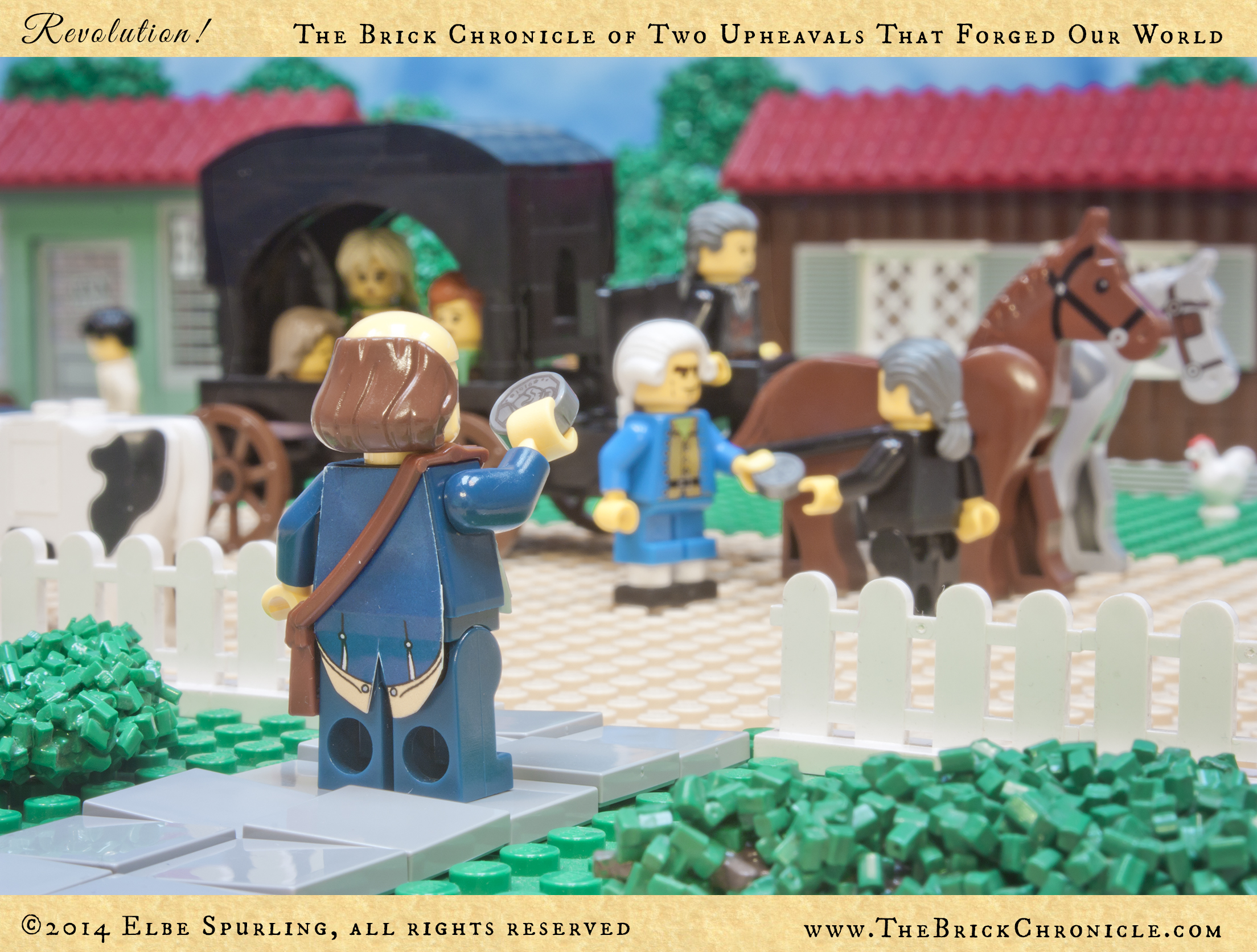

chapter_11_image_02

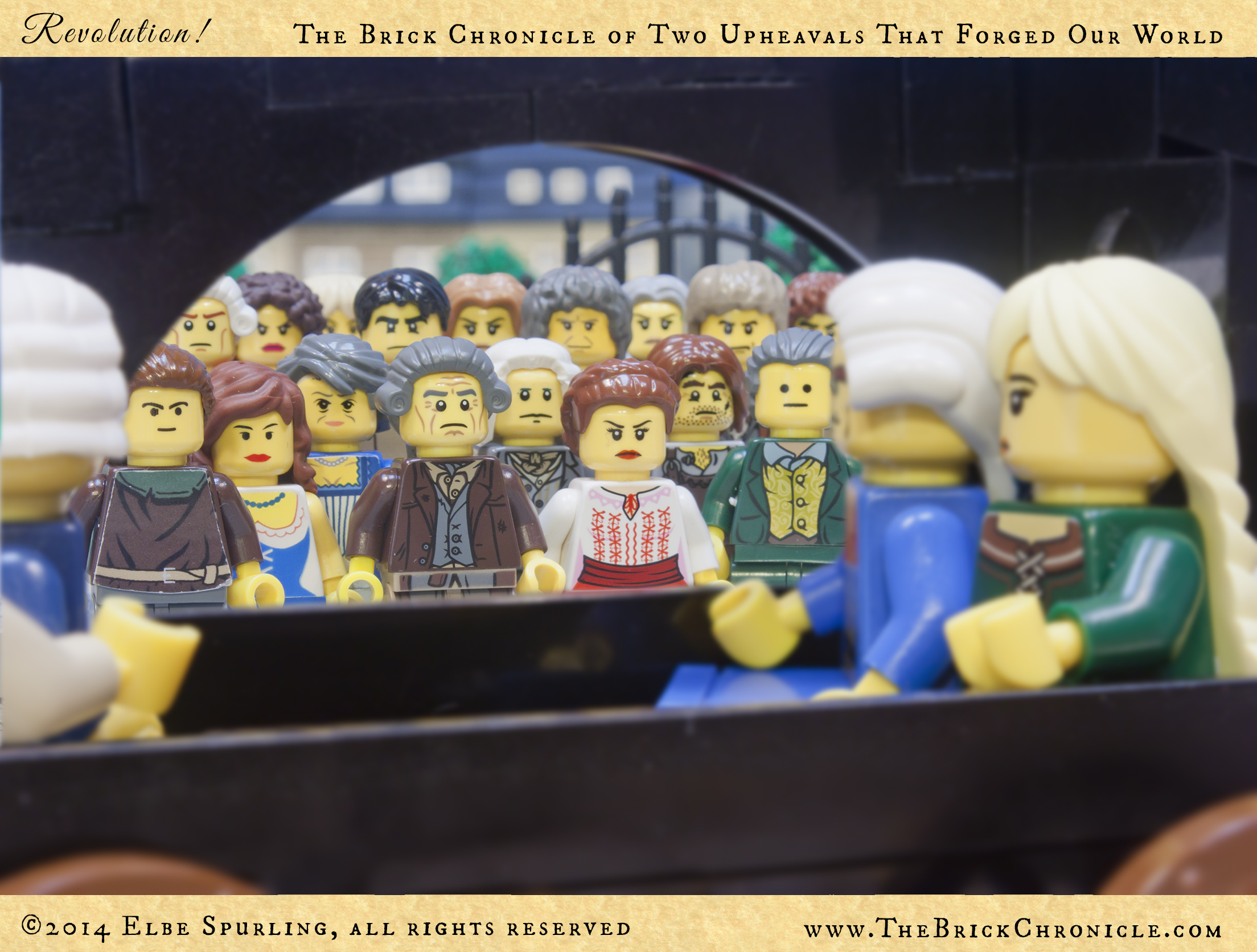

chapter_11_image_03

chapter_11_image_04

chapter_11_image_05

chapter_11_image_06

chapter_11_image_07

chapter_11_image_08

chapter_11_image_09

chapter_11_image_10

chapter_11_image_11

chapter_11_image_12

chapter_11_image_13

chapter_11_image_14

chapter_11_image_15

chapter_11_image_16

chapter_11_image_17

chapter_11_image_18

chapter_11_image_19

chapter_11_image_20

chapter_11_image_21

chapter_11_image_22

chapter_11_image_23

chapter_11_image_24

chapter_11_image_25

chapter_11_image_26

chapter_11_image_27

chapter_11_image_28

chapter_11_image_29