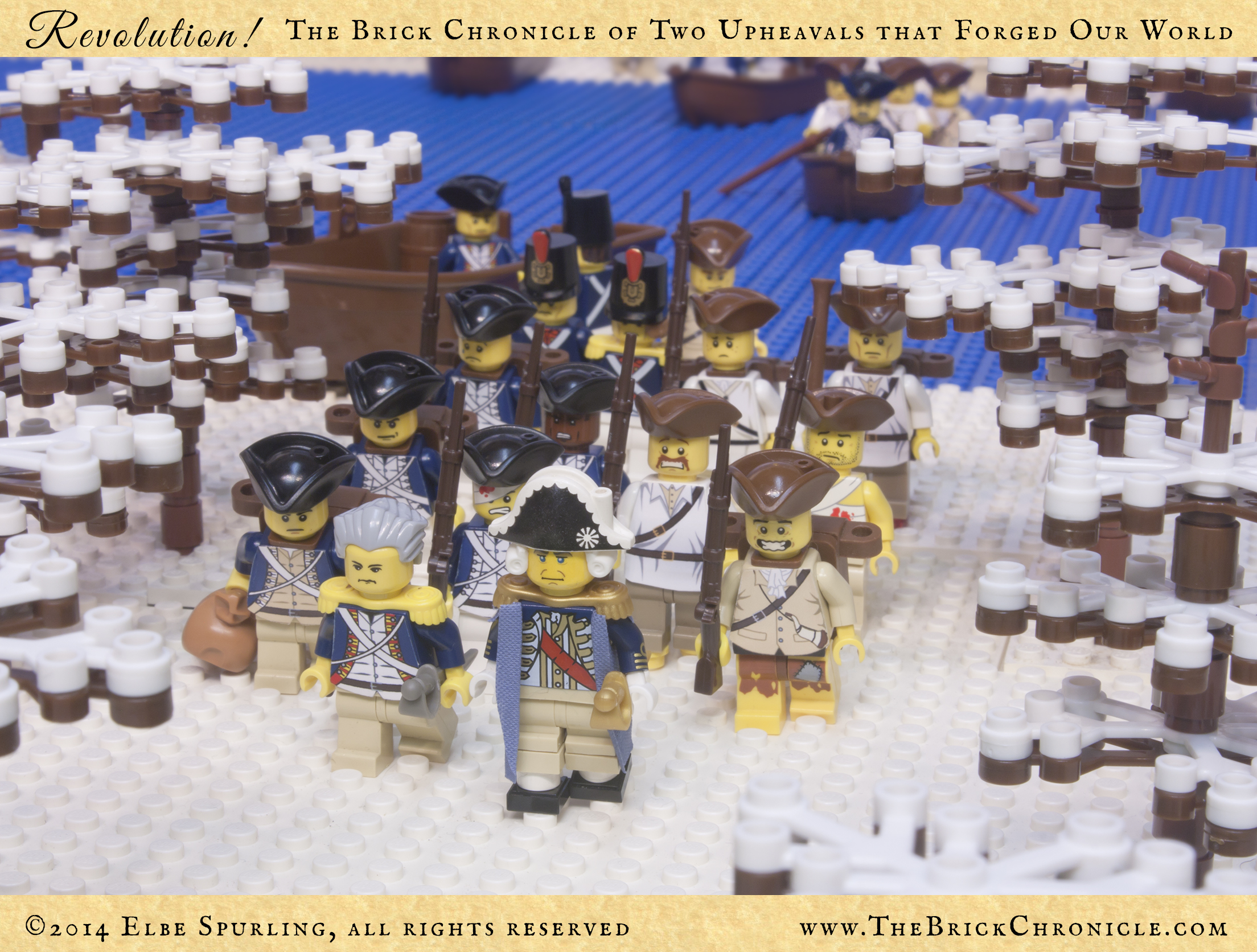

![General Howe landed troops in Westchester County in late October, attempting to cut off Washington’s escape route. At a major battle in White Plains, the rebels were again outflanked and forced to retreat amid heavy fighting. One Connecticut soldier witnessed a single cannonball that “first took the head of Smith, a stout heavy man and dash’t it open, then it took off Chilson’s arm . . . it then took Taylor across the bowels, it then struck Sergt. Garret of our company on the hip [and] took off the point of the hip bone . . . What a sight . . . those men with their legs and arms and guns and packs all in a heap.”](http://www.thebrickchronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/chapter_05_image_33.jpg)

Opening Quote

chapter_05_image_01

chapter_05_image_02

chapter_05_image_03

chapter_05_image_04

chapter_05_image_05

chapter_05_image_06

chapter_05_image_07

chapter_05_image_08

chapter_05_image_09

chapter_05_image_10

chapter_05_image_11

chapter_05_image_12

chapter_05_image_13

chapter_05_image_14

chapter_05_image_15

chapter_05_image_16

chapter_05_image_17

chapter_05_image_18

chapter_05_image_19

chapter_05_image_20

chapter_05_image_21

chapter_05_image_22

chapter_05_image_23

chapter_05_image_24

chapter_05_image_25

chapter_05_image_26

chapter_05_image_27

chapter_05_image_28

chapter_05_image_29

chapter_05_image_30

chapter_05_image_31

chapter_05_image_32

chapter_05_image_33

chapter_05_image_34

chapter_05_image_35

chapter_05_image_36

chapter_05_image_37

chapter_05_image_38