Opening Quote

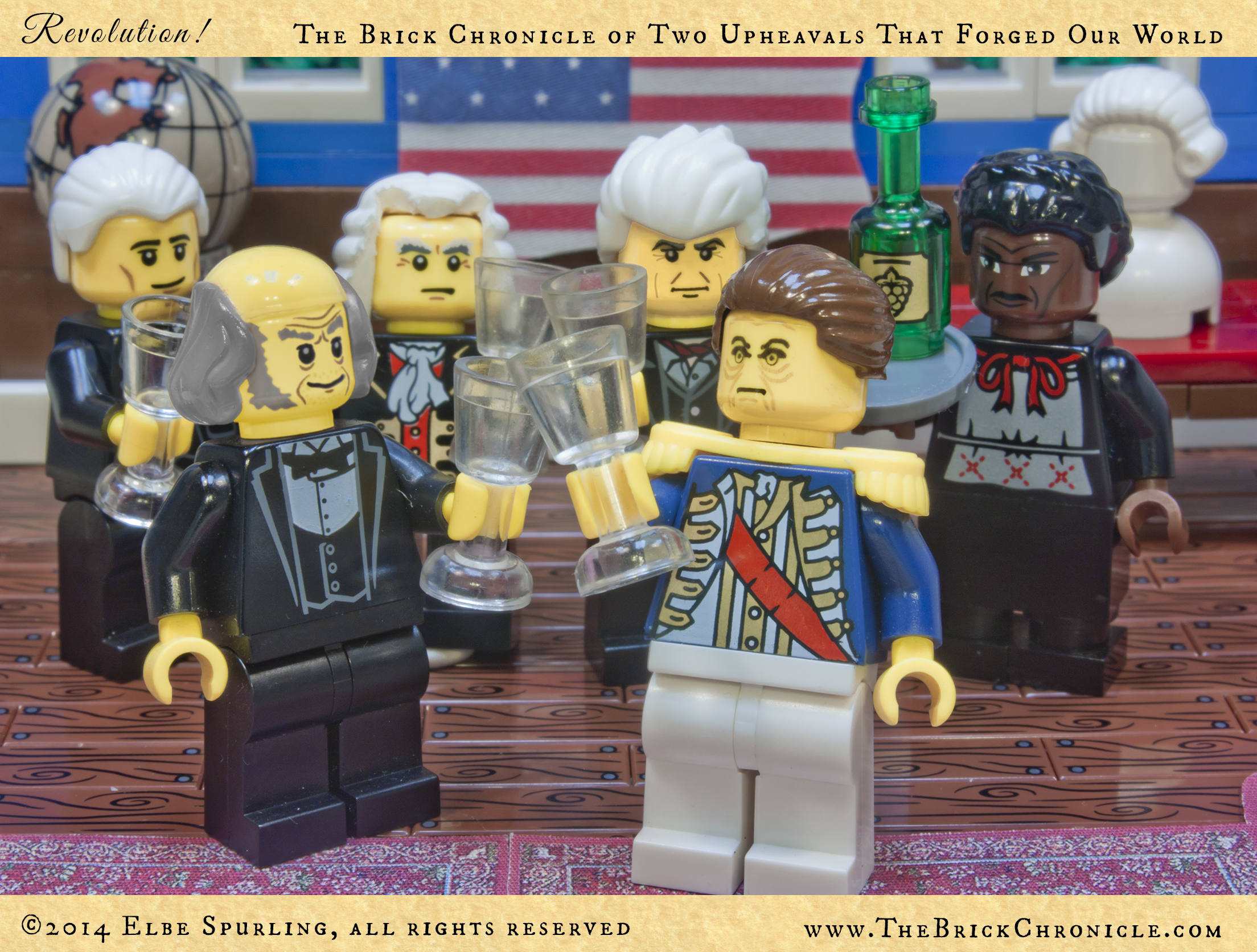

chapter_16_image_01

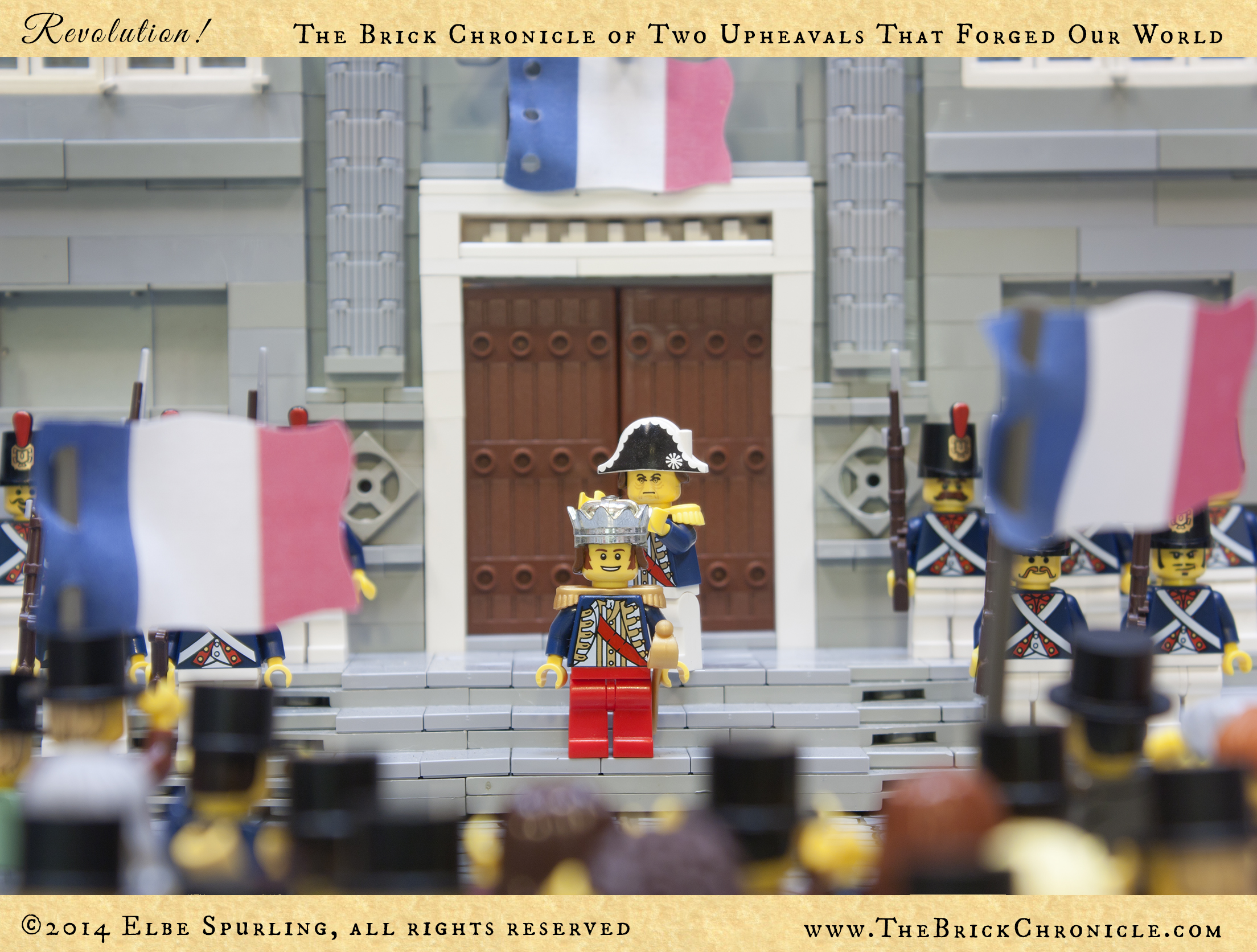

chapter_16_image_02

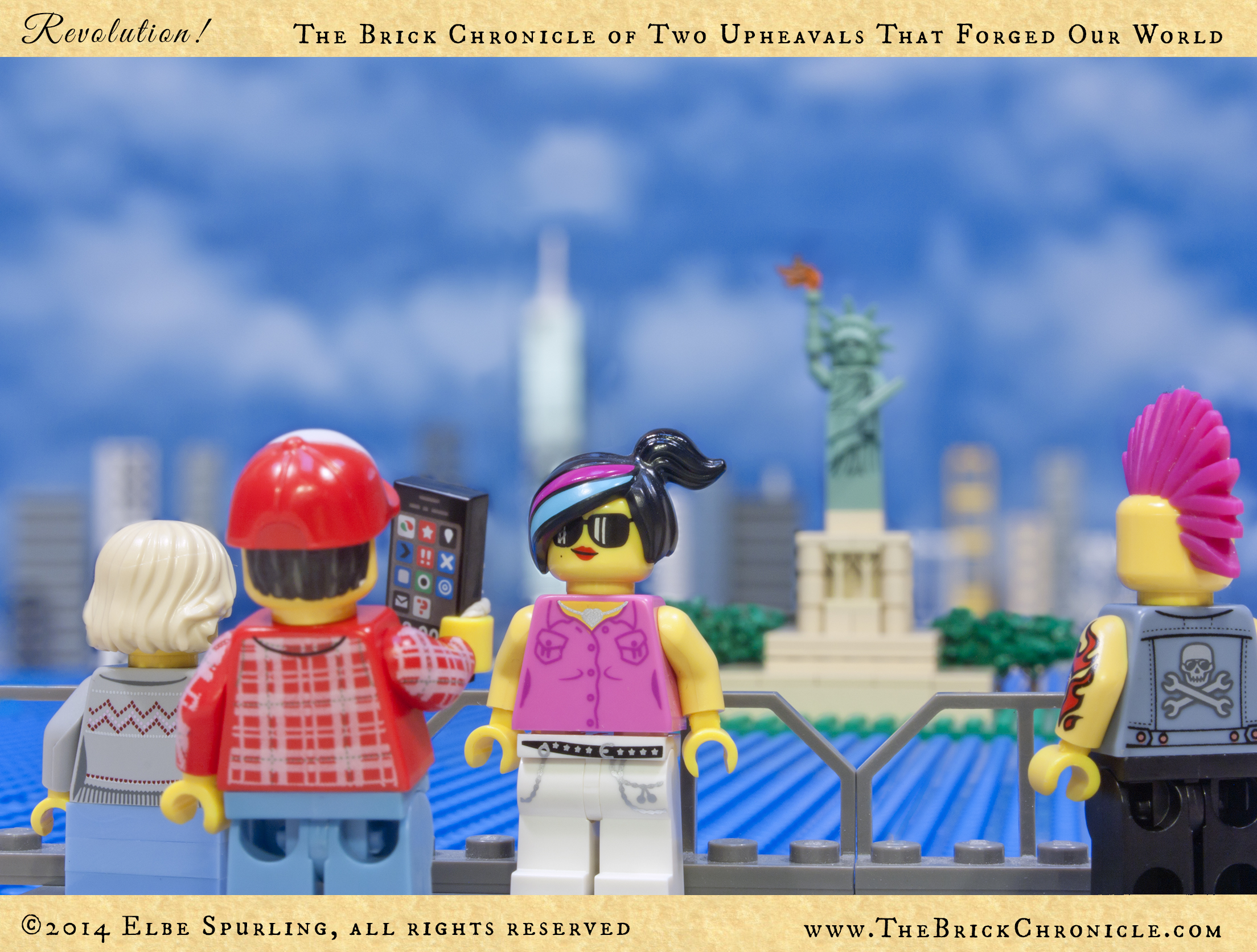

chapter_16_image_03

chapter_16_image_04

chapter_16_image_05

chapter_16_image_06

chapter_16_image_07

chapter_16_image_08

chapter_16_image_09

chapter_16_image_10

chapter_16_image_11

chapter_16_image_12

chapter_16_image_13

chapter_16_image_14

chapter_16_image_15

chapter_16_image_16

chapter_16_image_17

chapter_16_image_18